Your basket is currently empty!

The Syllabary: A Poem in 2,272 Parts

“La Kiuva

You’ll have seen old faces scoured till they shone

As apple blossom soured into fruit, oh, every time

I scowled at the tree that stood

Like a pupil who would not get one verb wrong.

No friend of pain, I scowed the deep,

Deep Field that Hubble plummeted;

If every stound of neural lightning

Coined another bright day out of me,

What would the tannic darkness do?

Well, a self that gets too fearful can be sloughed;

I’m snake enough for that. Sound in the dark.

The message in the bottle is the wine.”

Description

The Syllabary, begun in the 1990s and completed in 2023, put its ear to the ground and listened; it consists of 1,328 empty sounds and 2,272 spoken parts of 1 to 37 lines in length, each based on a cluster of between 1 and 47 monosyllabic words.

The Syllabary is a printed book in eleven volumes, with different complete sequences published in runs of 25 copies each.

It is also an audiovisual sequence at www.thesyllabary.com, which starts at random and leads the viewer to the next verse in any of three directions, ad infinitum.

And it is designed for physical installation in an urban setting.

In PN Review, Philip Terry writes:

“While the rest of us worry about the future of writing in the age of AI, the poet Peter McCarey has been busy creating his own breed of writing machines, more like the imaginary creations of William Heath Robinson than the slick machines of AI. McCarey has been doing this for some time – his volume Collected Contraptions appeared in 2011 – but his most recent work, The Syllabary (A Poem in 2,272 Parts), simultaneously published online and in book form (the book runs to eleven volumes), takes this to a new level. The result is one of the longest poems in the language, rivalling Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion of 1612, which ran to 15,000 lines.

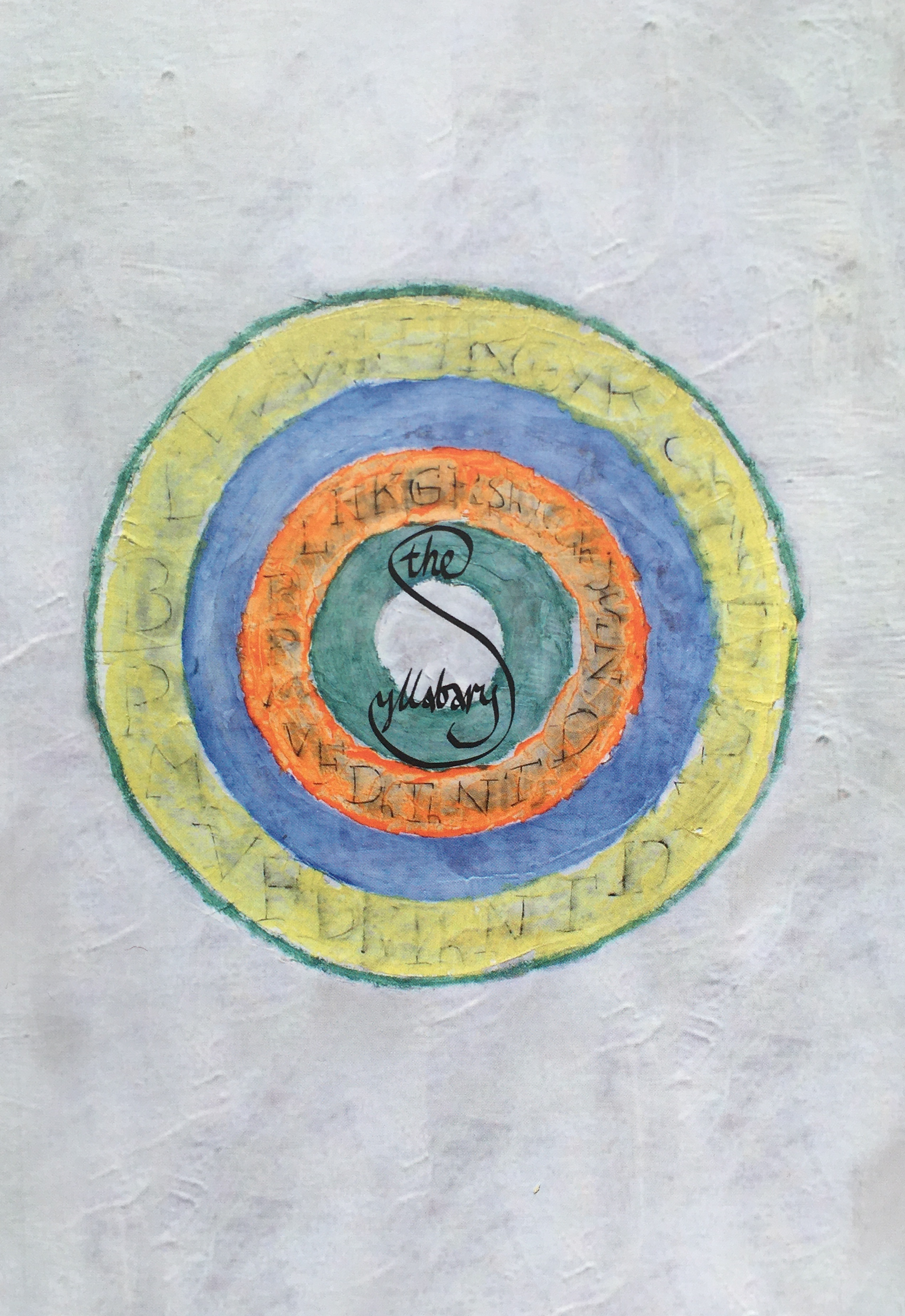

“In the Foreword to the printed version (a limited edition of twenty-five, each weighing around 5kg) McCarey cryptically describes the mechanism as follows: ‘The Syllabary sets every monosyllabic word of my ideolect in a matrix of 20 initials, 10 vowels and 18 terminal consonants or nonsonants. Of the 3,600 [20 x 10 x 18] cells in the matrix, 2,272 contain a word or cluster of words. There is a glyph to every cell, and a lyric to each word-bearing glyph.’ If this leaves you puzzled, the workings of McCarey’s machine become luminously clear when you read the online version of the book. Here the reader enters what at first seems like an endless labyrinth – a ‘3D map’ where there ‘is no telling where it will take you’ – but its fundamental mechanism quickly comes into focus. The first thing you see, turning to the bottom right-hand corner of the webpage, is a wheel, or three wheels, one inside the other, the outer wheel bearing consonants (the twenty initial consonants), the middle wheel vowels (the ten vowels), the inner wheel more consonants (the eighteen terminal consonants), and when the turning wheels come to rest they highlight a sequence of letters: HAM, LEB, HAL, YEL and so on. In the case of YEL (one of the 2,272 cells that contains a word), once the wheel stops, a handwritten glyph appears, spelling the word YELL, then we hear the poet read a poem generated by the word:

To yell at your colleagues

Is maybe cathartic

But not, in the long run,

That wise.

“On other occasions the three letters in the wheel give rise to more complicated glyphs, where by the insertion of additional letters, multiple words are created, as in YEARN, which is the basis of the poem ‘Yen’:

I yearn for you

But never learn. For you

I’d die my dear, but don’t.

“And then there are numerous poems which take this process as far as it can go, giving rise to complicated glyphs that by inserting extra letters create matrices of overlapping words. In the following example, the glyph

containing the words ‘gunge’, ‘gulch’, ‘grudge’, and ‘grunge’ forms the building blocks of the following poem:

There’s some gunge in the gulch

You could guddle for bargains

That nobody’d grudge you

So lee aff the grunge.

“The method, which you can begin to glimpse here, frequently gives rise to poems built around clusters of similar-sounding words, something which many traditional poets achieve by employing end rhyme, but here the music is created within the lines as well as at the end. This makes for an original and arresting soundscape, very different, in fact, from any use of rhyme, end rhyme or internal rhyme alike, for here the echoing sounds are constantly metamorphosing and diverging as we read. And it gives space to the reader, too, not just in allowing them to participate in the act of composition, by seeing the writing process as it unfolds, but in the latent suggestion that each poem, each word cluster, could be resolved in different ways, be rewritten by each reader. In a work containing 2,272 poems, inevitably some will be better than others. Several of the pieces here are throw-away two-liners, though even these are often infused with sardonic wit: ‘In the random snooker hall of physics / Life’s a glitch’. Occasionally, too, the poem strains to encompass the words thrown up by the machine, like a juggler presented with too many balls, but in the vast majority of cases, and triumphantly in others – as in the moving poem in memory of the poet Douglas Oliver – the poems rise to the occasion, at once enabled by, and transcending, the machine out of which they are born.”

(PN Review 278, from the essay “What is Poetry?”

Read more about The Syllabary:

Additional information

| Author | Peter McCarey |

|---|---|

| Format | Perfect bound, 11 volumes, 2288 pages. |

| First edition | Geneva, Maison Rousseau et Littérature with Molecular Press, 2023, ISBN 978-2-9701500-3-9 |

| Second edition | Geneva, Molecular Press, 2024, ISBN 978-2-9701500-4-6 |